Brady Perron

Profile and significance

Brady Perron is a New Hampshire–raised, Utah–based freeski athlete-turned-filmmaker whose eye and editing have helped redefine how park, street, and culture are presented on snow. He grew up lapping Mount Sunapee before moving west at 18, cutting his teeth with the 4bi9 and Stept crews and then shifting behind the lens full time. Across the last decade he’s become a cornerstone collaborator with Phil “B-Dog” Casabon and Jake “Mango” Mageau, directing and shooting projects that balance technical skiing with rhythm, pacing, and story. That approach earned back-to-back X Games Real Ski golds as the credited filmer for Casabon in 2018 and 2019, and formalized his role as a Director/DP with Level 1 Productions beginning in 2020. In 2021 he and Mageau released “Freehand,” followed by “Something in the Water” (2022) and ongoing Kimbo Sessions and invitational edits, culminating in new 2024–2025 releases that highlight his continued influence.

Perron matters because his films changed what “good skiing on camera” looks like. He privileges readability—angles that let the trick breathe, music choices that guide the eye, and cuts that amplify style instead of hiding behind pace. For fans, that’s why his work is rewatchable. For athletes, it’s why clips he directs tend to age well: the skiing is visible, the intent is clear, and the edit has soul.

Competitive arc and key venues

Though Perron is best known behind the camera, his competition relevance is real: he filmed and edited the winning X Games Real Ski entries for Phil Casabon in 2018 and 2019, an all-urban contest judged as rigorously as any slopestyle final. Those medals validate a method—pick lines that photograph well, favor decisive exits and held moments, and sequence the cut to tell the truth about difficulty. On the invitational side, his lens has become part of the language at Sweden’s Kimbo Sessions in Kläppen and at rider-driven gatherings where style and creativity lead. In 2021 he and Mageau launched “Freehand” with Level 1; in 2022 they returned with “Something in the Water,” and in 2024 Perron released a Kimbo short that captured the session’s tempo. Early 2025 added a fresh statement piece shot with Henrik Harlaut, reinforcing his role as a go-to director for the scene’s most influential skiers.

Geographically, these milestones map to specific venues. Broadcast-level courses at Aspen (Buttermilk) shape Real-series expectations for how street skiing should read on a big stage. Summer repetition at Timberline on Mount Hood trains the eye for long-lens timing and reliable speeds. And the SLC ecosystem—Brighton/Solitude rails, Park City jump lines, and the density of filmers and skiers—gives him the daily reps to keep ideas sharp when the camera is rolling.

How they ski: what to watch for

Perron’s skiing background bleeds into his direction. He favors tricks that “read”—locked presses, pretzels with edge authority, swaps that happen late enough to be unmistakable, and jump axes that set early so the grab has time to present. When he’s the one skiing for a shot, expect quiet shoulders, compact stance, and landings that roll immediately into the next feature. When he’s filming, expect framing that shows those same qualities in others: the camera holds just long enough for the viewer to feel pressure changes on rails or to see a grab fully connected. The result is an honest picture of difficulty and a heightened appreciation for style.

For progressing skiers, that’s instructive. You’ll see how a small choice—grab duration, a subtle nose press, a cleaner exit—impacts the clip more than adding another 180. Perron’s films are essentially a syllabus for “readable difficulty.”

Resilience, filming, and influence

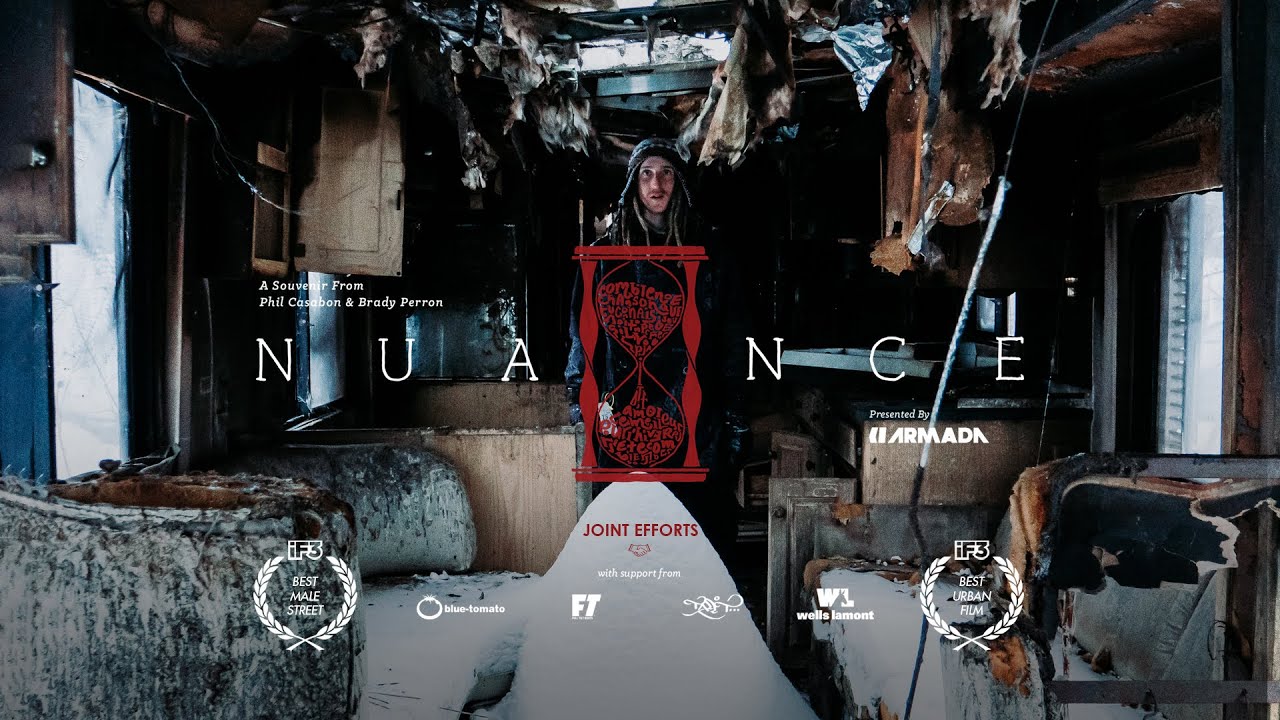

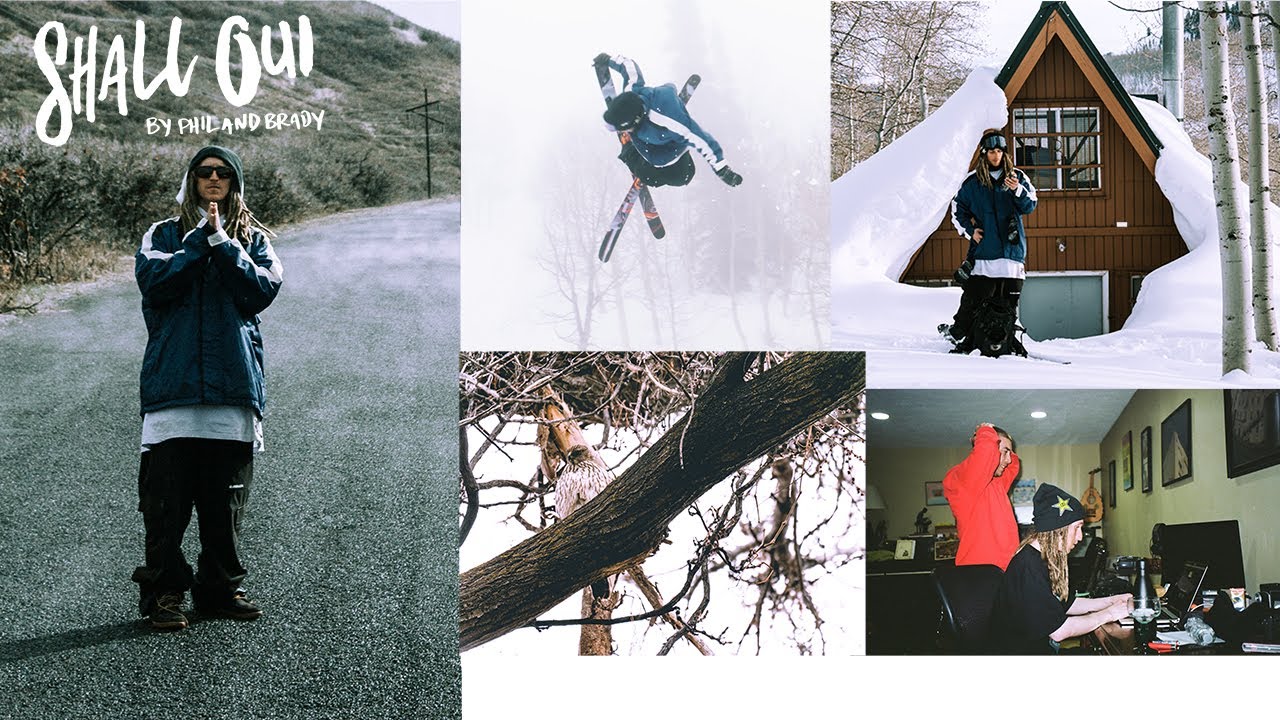

The shift from athlete to director wasn’t a retreat; it was a doubling-down on contribution. After early parts with 4bi9 and sessions with Stept, Perron helped steer flagship B-Dog projects—“Tempo,” “En Particulier,” “Nuance,” and “Ensemble”—that foregrounded choreography and mood. With Mageau, he crafted the intimate SLC-based “Freehand” (2021) and expanded the palette in “Something in the Water” (2022), a short that folded fly-fishing and road-life into the skiing without losing technical weight. In 2024 he delivered a Kimbo Sessions cut that bottled the event’s flow, and in 2025 he teamed with Henrik Harlaut on a new edit that shows his recent direction: warmer color, deliberate handheld energy, and musical choices that push narrative as much as tempo.

Influence shows up in two places. First, athletes now build lines with the “Perron lens” in mind—planning where a camera can sit, how a trick breathes, and what detail will be visible at speed. Second, younger filmers copy the cadence: steadier cuts, honest speed, non-gimmick music edits. The upshot is a healthier feedback loop between skiing and cinema: technique supports the shot, and the shot clarifies the technique.

Geography that built the toolkit

Perron’s toolkit is a product of place. Early repetition at Mount Sunapee’s compact terrain taught economy: get to features quickly, try often, and value control over amplitude. The Salt Lake City corridor added rails, urban options, and a year-round community that treats filming as training. Summer blocks at Timberline’s Palmer Snowfield gave him and his collaborators the cycle of “try → adjust → retake” that makes winter street clips possible. Abroad, sessions at Kläppen’s National Arena and New Zealand’s Cardrona parks contributed scale and rhythm—long lines where tricks must relate to one another and still read from the fence line. Broadcast venues like Buttermilk contextualized all of it: street moves can work live if the speed, angle, and axis are chosen for the camera, not against it.

Those places also explain the feel of his films: calm, confident speed; compositions that keep skis in the frame just long enough; and edits that make a run feel inevitable.

Equipment and partners: practical takeaways

Perron’s collaborations span core brands and production houses. As a Director/DP with Level 1 Productions, he has access to athletes and support structures that let ideas scale. Projects with B-Dog have involved Armada’s creative universe; the recipe there (whether on cam or in front of it) is durable twin-tips tuned for rail bite underfoot and detuned tips/tails, paired with a neutral mount that supports switch landings and butter entries. With Mageau, “Something in the Water” listed partners like 686, Fat Tire, and ON3P Skis, illustrating how modern films often weave athlete sponsors into a project’s backbone.

Takeaways for skiers and filmers alike: build a repeatable setup and a predictable workflow. On snow, that’s a ski you don’t fight, bevels you can trust, and a stance you can hold for ten takes. Behind the lens, that’s stable exposure, angles that don’t lie about speed, and music that supports—not overwhelms—the skiing. If your edit is clear, the style can breathe.

Why fans and progressing skiers care

Fans care because Perron’s work makes difficult skiing feel understandable without flattening it. You see the lock on a press, the moment a pretzel begins, and the axis change that separates a good double from a great one. Progressing skiers care because his films are roadmaps: how to sequence a line, where to place a caper trick, when to hold a grab, and how to translate park habits to street or vice versa. Coaches and judges care because the clarity helps calibrate what counts in 2020s freeskiing: readable difficulty, execution, and style that survives slow-mo and broadcast angles alike.

Most of all, Perron’s catalog shows that culture leaders don’t have to choose between art and accuracy. His Real Ski wins prove the method under pressure; his Level 1 work proves it scales; and his recent invitational edits prove it still evolves. If you want to understand where freeski filming and style are going next, watch what Brady shoots—and how he lets the skiing speak.

Quick reference (places)

- Utah — everyday training ground and filming hub (SLC corridor).

- Timberline (Mt. Hood) — summer laps and Palmer Snowfield repetition.

- Mount Sunapee — New Hampshire home hill foundation.

- Cardrona — Southern Hemisphere park venue for invitational edits.

Principal sponsors

- Level 1 Productions — director/DP representation and production partner

- Armada — long-running creative collaborator across B-Dog projects

- ON3P Skis — project support (e.g., “Something in the Water” with Mageau)

- 686 — film sponsor (outerwear partner on Mageau collaborations)