Mt. Baker Ski Area

Washington

United States

Overview and significance

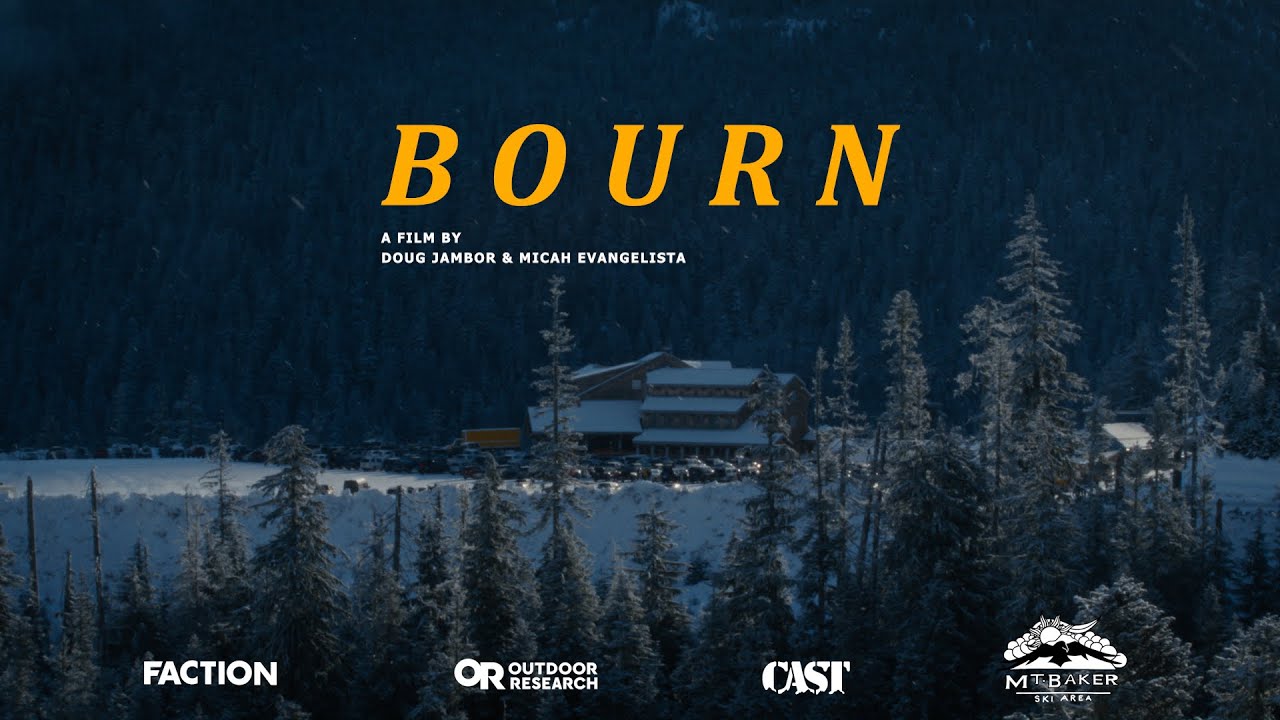

Mt. Baker Ski Area is a cult-classic powder mountain in the North Cascades of Washington State, near the small community of Glacier and about a 75-minute drive east of Bellingham. It sits within the Mt. Baker–Snoqualmie National Forest at the end of State Route 542, with two main base areas, White Salmon and Heather Meadows, and chairlifts climbing to around 1,550 metres (just over 5,000 feet). On paper, Baker is a mid-sized resort: roughly 1,000 acres of skiable terrain, around 1,500 feet of vertical, and 10 lifts (eight fixed-grip quads and two rope tows). On snow, it rides much bigger, thanks to complex terrain, huge snowfall and easy access to backcountry bowls and ridges.

Baker’s fame comes from snow and terrain rather than luxury infrastructure. The ski area claims one of the highest average lift-served snowfalls in the world—around 16 to 17 metres (roughly 650 inches) per season—and still holds the all-time single-season record of about 1,140 inches from the winter of 1998–99. Storms roll in off the Pacific and stack up against the North Cascades, dropping massive, often heavy “Cascade concrete” that fills in gullies, pillows and natural halfpipes. There’s no on-mountain lodging, no big village, and no snowmaking; this is a day-use mountain built almost entirely around the cycles of real weather.

For freeskiers, Mt. Baker is a reference point. The in-bounds terrain is steep, playful and barely groomed in places, with natural spines, wind lips and drops everywhere you look. The surrounding sidecountry and backcountry—names like Hemispheres, Shuksan Arm and the Canyon—have appeared in countless film segments. Snowboard culture here is equally strong, anchored by events like the Legendary Banked Slalom and a deep local scene. For the skipowd.tv universe, Baker is one of those mountains that define what storm riding, natural features and big-snow freeride really look like.

Terrain, snow, and seasons

Mt. Baker’s terrain sprawls across multiple ridges and bowls above its two base areas. White Salmon, at roughly 3,500 feet, and Heather Meadows, higher up, both feed into a web of fixed-grip quads labelled simply by number rather than name. The overall vertical is about 1,500 feet from base to top, but the way the chairs are stacked means you can link several pitches into long, flowing laps or focus on shorter, steeper faces for repeated hits.

Official stats list about 1,000 acres and roughly 30–40 named runs, but that barely hints at how much is skiable within the resort boundary. Only around a quarter of the terrain is classed as “easiest,” with almost half rated as intermediate and about a third tagged as advanced or expert. In practice, even many “blue” runs feel more like freeride canvases than standard groomers, with rolls, side hits and short steep pitches threading through dense subalpine forest and rocky terrain.

Signature in-bounds areas include the Pan Dome and North Face terrain off Chairs 1 and 6, the steep pitches and natural halfpipes accessible from Chairs 5 and 8, and the gullies and drops under the Shuksan side. Grooming is selective; Baker tends to set up a handful of machine-worked routes each night and leave large sections to fill naturally. This preserves the mountain’s character and makes it ideal for skiers and riders who love variable snow, wind features and natural transitions.

Snow is Baker’s calling card. Long-term averages hover around the mid-600-inch mark, and many winters blow well past that. Storm frequency is high, and refills of 15–30 centimetres are common; multi-foot dumps happen regularly during peak season. The snowpack is maritime, which means denser than the ultra-light powder found in interior ranges, but that density helps bury rocks, build stable takeoffs and create smooth, surfy landings in natural features. It also makes tree wells, sluffs and wet-slab avalanche problems serious considerations on heavy-snow days.

The typical lift-served season runs from mid- or late November into late April, depending on when big storms arrive and when the snowpack finally starts to lose depth. There is no night skiing; operating hours usually sit around 9:00 to 15:30. Early season can deliver full-on powder if November storms hit, but mid-December through March is the most reliable window for deep coverage across all aspects. Spring brings longer days, corn cycles on solar slopes, and still-wintry snow on shaded faces and in high pockets after late storms.

Park infrastructure and events

Mt. Baker has historically focused on natural terrain rather than heavily sculpted parks, but it does offer freestyle-specific spaces. A Freestyle Feature Zone, introduced off Chairs 3 and 4, concentrates boxes, rails and small jumps on a dedicated slope. The setup changes through the season but typically includes jib lines, rollers and creative snow features built to work with Baker’s natural undulations. Some seasons also see a small rail garden or progression area near beginner zones to help new riders discover freestyle in a lower-consequence environment.

That said, the “park” most riders talk about here is the mountain itself. Cornices, wind lips, pillows, gullies and natural step-downs form a huge, organic slopestyle course across the resort. On storm days, locals session specific features—wind-loaded spines, natural gaps, road hits along the access highway—rather than spending all their time in a conventional park lane. The mix of deep snow and sharp terrain makes it ideal for stylish airs, slashes and butters that blend freeride and freestyle into one line.

In terms of events, Baker is best known for the Legendary Banked Slalom, a snowboard race that has run since the mid-1980s in a natural halfpipe near the resort. While it is snowboard-only, the event has huge cultural crossover into skiing: film crews, skiers and riders from around the world converge on the mountain that week, and the course itself is a perfect example of how Baker shapes snow into flowing, high-bank tracks rather than manicured FIS-style features. Beyond that, Mt. Baker hosts youth freeride and freeride-inspired programs, film premieres and grassroots gatherings that focus more on community and storm chasing than on strict contest formats. Freeski film crews such as Blank Collective Films regularly use Baker’s cliffs, pillows and storm light as a backdrop, further cementing its status in the freeride imagination.

Access, logistics, and on-mountain flow

Mt. Baker is a true end-of-the-road mountain. You reach it by driving State Route 542 (the Mt. Baker Highway) from Bellingham through small communities like Nugents Corner, Maple Falls and Glacier until the road literally ends at the ski area. There is no town at the base: lodging is down-valley in Glacier, Maple Falls, Deming or Bellingham, with a scattering of cabins and rentals along the highway. On storm days, the drive can be slow and snowy, and occasional closures or chain requirements are part of normal operations, so trip plans must build in weather margin.

Once you arrive, logistics are simple but old-school. You park at White Salmon or Heather Meadows, buy or present your lift ticket at the lodge and walk a short distance to the lifts. There is no large central village; amenities are focused in the two day lodges and the Raven Hut mid-mountain lodge. Food is straightforward, and rental and repair services are mostly geared toward getting you out the door quickly rather than running a shopping mall.

The lift network is extremely efficient for skiers who like to move. Fixed-grip quads keep speeds moderate, but the chairs are short and the mountain is compact, so lap times are quick. From White Salmon and Chair 7 you can access longer groomers and the entrances to the Hemispheres and Shuksan Arm backcountry zones. Heather Meadows and Chairs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 feed steeper in-bounds pitches and natural gullies, with mid-station options that let you lap specific faces without skiing all the way to the bottom. The absence of sprawling base-to-base gondolas or flat traverses means you spend a very high percentage of your day actually skiing.

Local culture, safety, and etiquette

Mt. Baker’s culture is deeply local and strongly freeride-oriented. There is no slopeside real-estate scene and no big corporate village—just Washington skiers and riders who drive up, ride hard and head back down. The parking lots feel like gatherings of long-time pass holders, families and dedicated crews who have been lapping the same lines for years. You will see plenty of big, rockered skis and powder boards, duct-taped outerwear that has survived a decade of storms, and dogs napping by the bumpers of old Subarus and pickup trucks.

This stripped-down vibe goes hand-in-hand with a serious safety culture. Baker’s huge snowfall and steep terrain create substantial avalanche hazards, especially along ridge lines and near the resort boundary. Within the ski area, patrol works aggressively with control work and closures, and rope lines are enforced. When ropes are up, they are up for a reason; ducking them is frowned upon by locals and can result in losing your pass. Even in-bounds, tree wells, deep snow immersions and sluff management require attention, particularly during and immediately after big storms.

Beyond the ropes, Mt. Baker is surrounded by famous backcountry terrain that has featured in many film segments and guidebooks. The Hemispheres, Shuksan Arm and Table Mountain zones are all easily accessed from lifts, but once you cross the boundary you are on your own, in avalanche terrain that is not controlled or patrolled. Travelling there demands full backcountry kit—avalanche transceiver, shovel, probe—and the skills to use it, plus experience reading the Northwest Avalanche Center forecasts and moving safely in a deep, often stormy snowpack. Hiring a local guide service is highly recommended if you are new to the area.

On the etiquette side, Baker operates very much on “ride hard, be respectful” principles. Keep your speed in check near lift lines and beginner zones, call your drops clearly when you hit obvious features, and pay attention to people coming from above in tight chutes or narrow gullies. In busy storms, sharing lines, regrouping in safe zones and giving space in traverse tracks keeps the day fun for everyone. The mountain’s no-frills, community-driven identity depends on visitors slotting into that flow rather than trying to turn it into a park-only or high-luxury destination.

Best time to go and how to plan

The sweet spot for most Mt. Baker trips runs from early January through early March. By then, the base is typically deep across all aspects, and the odds of repeated powder cycles are high. December can offer huge early dumps and surprisingly good coverage, but it can also see warmer storms with rain up to mid-mountain. Late March and April shift toward spring skiing, with corn cycles on sunnier slopes, but deep snowpacks mean powder is still possible after late storms, especially on north-facing terrain.

Planning a Baker mission is less about booking a fancy package and more about staying flexible around storm tracks. Many riders base themselves in Bellingham to access restaurants, nightlife and services, then day-trip up the highway when the snow and road conditions line up. Others choose rental cabins or lodges in Glacier or Maple Falls to shorten the drive and immerse themselves more fully in the mountain rhythm. Because there is no lodging at the base, you will be driving every day you ski; winter tyres, chains and a vehicle capable of handling heavy snow are key.

It is smart to build weather buffers into your itinerary. High-precipitation storms can bring both feet of snow and rain-on-snow events that temporarily shut down parts of the mountain or the access road. A flexible schedule—three or four potential ski days for every two “must-ski” days—lets you pounce when the snow is right and gives you the option of off-days in Bellingham or along the coast. Checking the official snow report and Washington State road information each morning becomes part of the ritual.

Why freeskiers care

Freeskiers care about Mt. Baker because it embodies the raw, storm-powered version of resort skiing that many films hint at but few places deliver so consistently. It is a mountain where 50-centimetre overnight totals are not rare, where natural halfpipes and pillow fields sit directly under the chairs, and where you can spend entire days improvising lines through wind-sculpted features rather than following manicured park builds. The vertical is modest on paper, but the intensity of each lap—and the sheer depth of the snow—make every run feel consequential.

There is also the cultural weight. Riding at Mt. Baker plugs you into decades of Pacific Northwest ski and snowboard history: early alpine races in the 1930s, the birth of the Legendary Banked Slalom, and modern freeride segments from crews like Blank Collective Films that showcase the mountain’s cliffs, pillows and storm-light textures. For skipowd.tv’s audience, Baker is less a one-off destination and more a benchmark. It is the place you compare other storm mountains to, the hill that shows what “deep” really means, and the terrain that reminds you how much fun it is when the park, the freeride zone and the backcountry all bleed into one big, snow-choked canvas.