Trevor Hattabaugh

Profile and significance

Trevor Hattabaugh is an American freeski athlete who quietly blended high-level halfpipe results with a later pivot toward film projects and all-mountain freeskiing. Raised in Boise, Idaho, he first learned to ski at Bogus Basin, where a strong local freestyle program helped him into moguls, aerials and slopestyle before long. When that program shut down he shifted to the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation, spending his high school years skipping Friday classes to ride the lifts at Sun Valley Resort and refine his park and pipe skills. Those long days paid off: by age nineteen, after moving to Salt Lake City for college, he had climbed to around 20th in the world and inside the top ten in the United States in men’s halfpipe on the AFP rankings, earning invitations to World Cup starts and a spot on the U.S. team for the FIS Freestyle Junior World Ski Championships in Valmalenco, Italy.

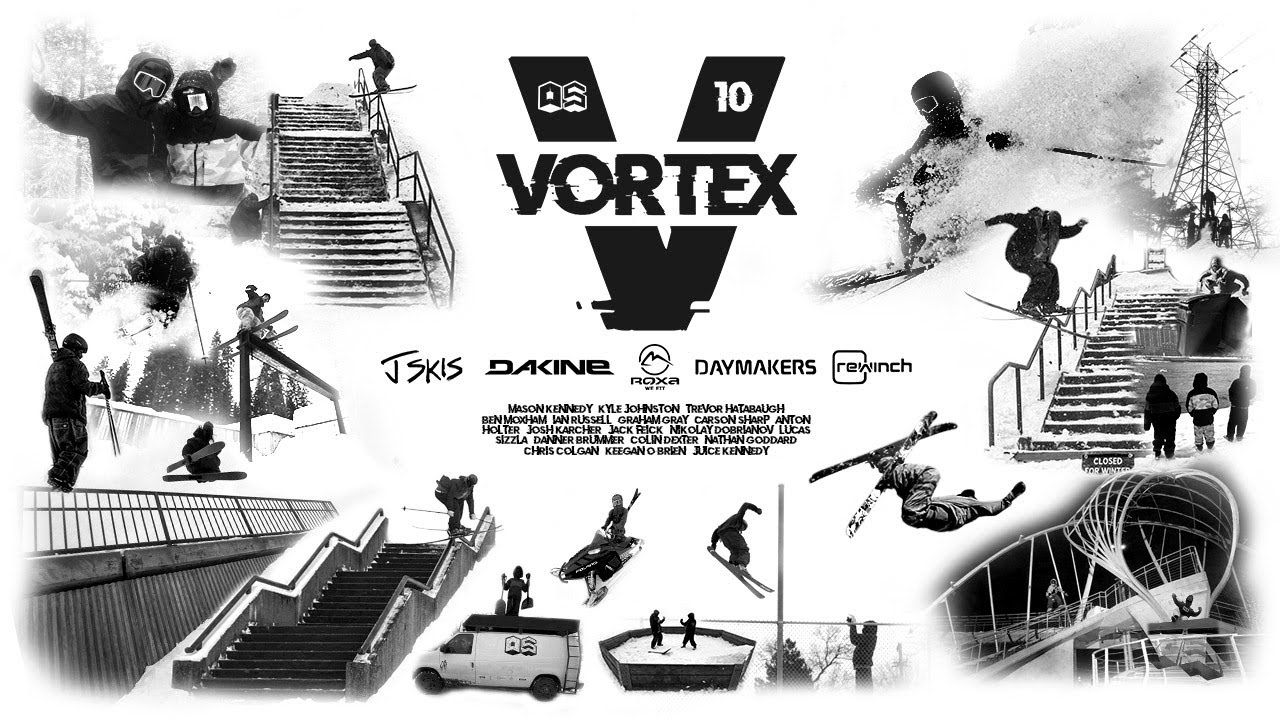

Hattabaugh’s significance inside freeski culture comes from the way he used that competitive foundation as a springboard into a broader life in skiing. A serious knee injury at the Mammoth Grand Prix ended his first World Cup chapter just as it began, but instead of walking away he doubled down on coaching, film segments and deep-snow skiing. As a team athlete for boutique ski brand Crosson, with a full segment in OnSlaught’s street-and-park movie “Activate” and later appearances in the crew film “Twenty Twenty” and the OS Crew project “VORTEX,” he became part of the independent film ecosystem that drives much of modern freeski progression. For fans who follow both contest pipelines and DIY movie crews, he stands out as an example of how a racer-style work ethic can coexist with a more creative, film-driven vision of the sport.

Competitive arc and key venues

The competitive arc of Trevor Hattabaugh’s career runs through many of the classic proving grounds in North American freestyle. After switching from Bogus Basin’s cancelled program to the Sun Valley team, he raced through USASA events and regional halfpipe starts, piling up repetitions in the pipe under the guidance of the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation. A breakthrough came when he was named to the U.S. team for the 2014 Freestyle Junior World Ski Championships, representing Boise and SVSEF in men’s halfpipe on the Valmalenco, Italy venue against the strongest juniors in the world. Around the same period, he appeared at open events such as the Aspen Snowmass Freeskiing Open, reinforcing his place among the deeper field of North American halfpipe specialists.

By nineteen, now living in Utah and studying at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Hattabaugh’s AFP rankings told the story: roughly 20th in the world and 10th in the United States in men’s halfpipe, with a third-place finish at USASA Nationals in the Men’s Open division creating momentum toward the sport’s highest level. A World Cup invitation followed, but the Mammoth Grand Prix stop turned into a turning point for the wrong reasons when a crash in the pipe tore his ACL and MCL. That injury effectively paused his push toward Olympic-qualifying circuits, but it also opened the door to a different role. He stepped into coaching with Park City Ski & Snowboard, sharing his expertise with younger park and pipe athletes while quietly rebuilding his own confidence and redefining what success in skiing would look like.

How they ski: what to watch for

In clips from his competitive years, Hattabaugh skis the halfpipe with a classic, technically sound style that still reads well today. He approaches hits with measured speed rather than desperate pumping, staying tall and stacked over his boots as he climbs the wall. His spins emphasize clean axes and solid grabs over sheer spin count, with left- and right-side hits showing a willingness to work on both directions rather than relying only on a strong side. Landings are typically placed high enough on the wall to maintain flow into the next hit, a detail that judges appreciate and that viewers can study when learning how to keep a pipe run fluid instead of stalling between tricks.

As his focus shifted away from rankings, his skiing became less about scoring formula and more about expression across the mountain. Season edits show him taking that same pipe discipline into jump lines and all-mountain features, using solid pop and stable body position to keep rotations on axis even when the takeoff is less than perfect. When you watch his older segment in “Activate” or his shots in “Twenty Twenty” and “VORTEX,” look closely at how he manages speed into hand-built jumps, keeps his shoulders calm during spins and maintains a centered stance on landings so he can immediately link into the next feature. It is the same toolkit that carried him into the top twenty of the AFP rankings, repurposed for a looser, more creative format.

Resilience, filming, and influence

Resilience is a throughline in Hattabaugh’s story. Tearing a knee at a major Grand Prix just as a World Cup career is beginning is the sort of setback that convinces many athletes to step away for good. Instead, he used recovery time to reassess his goals and came back to the sport in multiple roles: coach, film skier and later big-snow explorer. Taking a job as a halfpipe coach with Park City Ski & Snowboard, he spent four winters helping younger athletes navigate the same terrain he had just left, bringing an insider’s understanding of run construction, pressure management and the realities of balancing school, training and travel.

Parallel to that structured coaching life, Hattabaugh kept a foot firmly planted in the independent film world. His Crosson athlete biography highlights a full segment in the OnSlaught movie “Activate,” and his name appears again in the iF3-listed “Twenty Twenty” project that followed the crew through a chaotic season. More recently, he joined Boise-based OS Crew for their tenth annual film “VORTEX,” a street-and-powder mix supported by companies such as J Skis, Dakine and Roxa Boots. Those projects do more than simply showcase tricks; they connect his story back to Boise and the Idaho–Utah corridor, giving younger riders from smaller markets a tangible example of someone who carried contest experience into long-form creative skiing.

Geography that built the toolkit

The geography of Hattabaugh’s life in skiing explains much of how he rides. Growing up in Boise meant that Bogus Basin was his laboratory, a community-focused hill where a strong freestyle program once gave local kids access to jumps, rails and coaching without the atmosphere of a mega-resort. When that program ended, weekend and Friday-off pilgrimages to Sun Valley Resort took over, exposing him to longer vertical, higher-spec parks and a culture of serious yet playful skiing that has shaped generations of Idaho freestylers. Those drives between Boise and Sun Valley became central to his teenage years, and it shows in the mix of work ethic and joy he brings to the hill.

Later chapters added more maps to his internal atlas. Moving to Salt Lake City immersed him in the Wasatch, with world-class terrain at Park City Mountain, Brighton and other nearby resorts feeding his training days while he studied at the University of Utah. A standout memory he often cites is skiing late-winter pipe laps at Cardrona Alpine Resort in New Zealand, discovering the uncanny sensation of mid-August winter in the Southern Hemisphere. He has also looked toward Montana—specifically Whitefish—as a base for a more powder-and-film-oriented phase of life, a natural progression for someone who has already checked the boxes of junior worlds, Grand Prix starts and coaching in one of North America’s core park-and-pipe hubs.

Equipment and partners: practical takeaways

As a member of the Crosson athlete team, Hattabaugh rides equipment that reflects both his park roots and his newer all-mountain ambitions. His favorite model, the Imperium 177, is described as a lightweight yet durable ski built to handle rails, rocks and big jumps without sacrificing the low-weight feel you want when boot-packing a couloir or hiking for a late-day lap. That balance between toughness and touring-friendly weight is unusually important for a skier whose time is split between resort park laps, sidecountry lines and film trips where carrying skis on the back is part of most days.

The practical takeaway for progressing skiers is less about the exact model and more about the philosophy behind his gear choices. Hattabaugh values skis that are forgiving enough to survive abuse but precise enough to reward good technique, paired with boots and bindings that hold up to halfpipe transitions and hard park landings. On the safety side, his backcountry-oriented plans presuppose a full avalanche kit and the training to use it, especially as independent film crews push deeper into off-piste terrain. For anyone building their own setup, his example argues for coherent quivers: a primary ski that truly matches the terrain and style you ride most often, and an equipment strategy that lets you explore powder, park and travel without constantly worrying about gear failure.

Why fans and progressing skiers care

Fans of freeskiing care about Trevor Hattabaugh because his path illustrates more than one way to “make it” in the sport. He never became an Olympic headliner, but he reached a level—top-twenty in the world in halfpipe, Junior Worlds selection, Grand Prix starts—that proves how far dedication and regional programs can take a motivated skier from Boise. When injury closed the door on a straightforward World Cup career, he redirected that same drive into coaching the next generation and stacking film clips with independent crews rather than walking away from skiing altogether. That resilience resonates with riders who understand that not every career follows a straight line from youth team to podiums.

For progressing skiers, his story provides a practical template. Master the basics in whatever pipe or park you can access, seek out strong coaching when possible, and be willing to pivot—toward film, coaching or new terrain—when circumstances change. Watch his older halfpipe edits to study clean, repeatable trick mechanics, then follow his movie segments in “Activate,” “Twenty Twenty” and “VORTEX” to see how those same fundamentals translate to urban setups and creative jump lines. In doing so, you get a fuller picture of what a lifelong relationship with freeskiing can look like: technically grounded, geographically adventurous and open to new roles as the sport, and the skier, evolves.