Jack Feick

Profile and significance

Jack Feick is a multi-talented freeski athlete, filmer and coach who connects the dots between big-mountain freeride, street skiing and independent film. Raised around Lake Tahoe in California, he spent his early years competing and later coaching on the Squaw Big Mountain Team at what is now known as Palisades Tahoe, before moving to Bozeman, Montana to study film at Montana State University and ski-instruct at the private Yellowstone Club. That mix of high-level freeride coaching, academic film training and access to some of the most playful terrain in the Rockies has given him a rare, 360-degree view of what skiing can be.

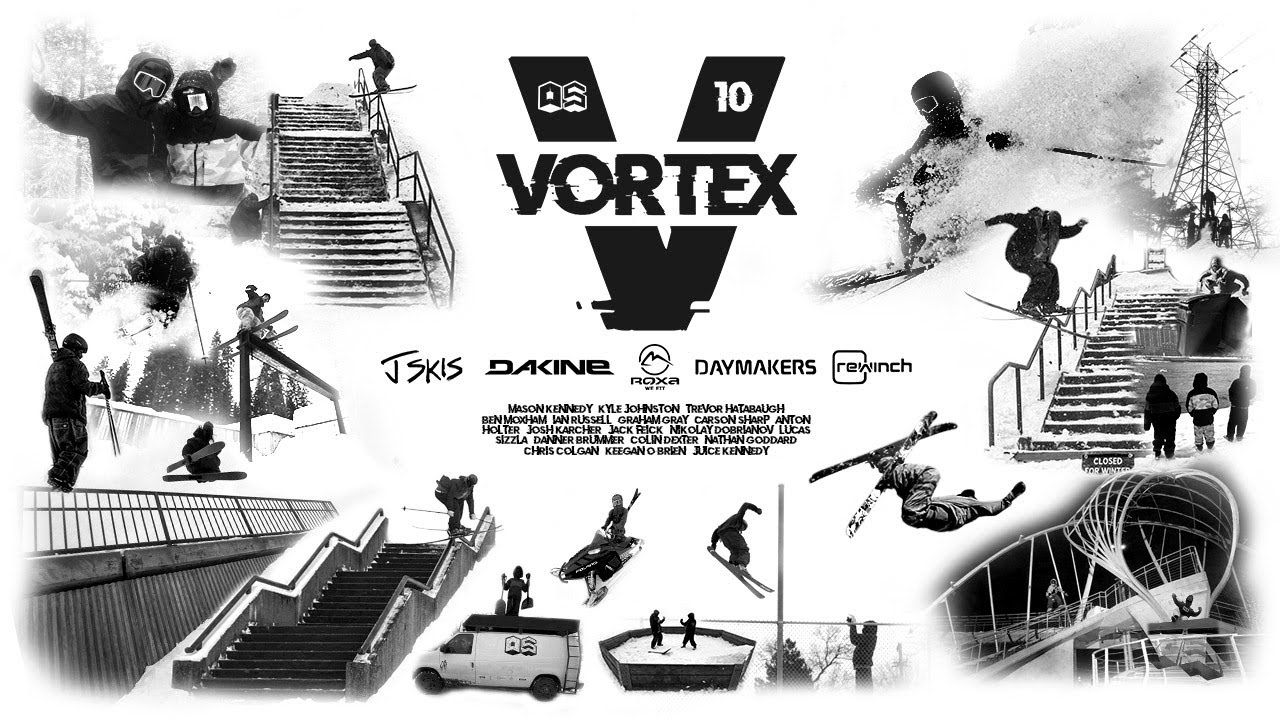

Feick is widely recognized in core circles for his work with two overlapping crews. In Montana, he directs and edits the “Montana Bandits” series, including the 37-minute film “Bandits Unchained,” a rowdy love letter to the state’s backcountry zones that features him both in front of and behind the camera. On the urban and park side, he is a key rider and contributor for Boise-based OS Crew, with standout street segments in their West Coast street project “FUEL” and a “very unique part” in the full-length film “TWENTY TWENTY,” followed by appearances in later OS projects up to and including “VORTEX,” their tenth annual movie. Add in a Freeskier “Photo of the Week” shot of him blasting a grab over sun-baked snow at Mt. Hood and recent travel clips from New Zealand’s Treble Cone, and you have an athlete whose influence spreads through film festivals, editorial features and online edits rather than contest podiums.

Competitive arc and key venues

Unlike many modern freeski names, Feick’s competitive arc runs primarily through big-mountain youth circuits rather than slopestyle and big air tours. As a teenager he skied and competed with the Squaw Big Mountain Team, lining up at events such as Sugar Bowl big-mountain competitions and learning how to pick lines, manage exposure and impress judges who care as much about fluidity and control as they do about tricks. That experience led naturally into coaching; he spent two seasons working with 10–14-year-old athletes on the same team, a sign that his mentors trusted not only his skiing, but also his eye for line choice and risk management.

From there, the venues that matter most become creative rather than strictly competitive. In the OS Crew universe, Feick’s name appears on rider lists and film blurbs for projects like “TWENTY TWENTY” and “FUEL,” where the crew spent a season traveling up and down the West Coast stacking mostly street shots in cities and resort towns. Those films have screened at events like the iF3 FUEL program and in regional tours, putting his skiing in front of live audiences across North America. In Montana, “Bandits Unchained” and earlier Montana Bandits projects cement him as a central figure in a loose collective of riders exploring backcountry terrain around Bozeman and beyond. Season after season, he keeps returning to the same core venues—Tahoe, Montana, Hood, the New Zealand Southern Alps—but each time with a slightly different lens, whether as athlete, director, coach or all three at once.

How they ski: what to watch for

Feick’s skiing blends freeride line sense with a relaxed, freestyle-informed touch. In Montana Bandits footage you see him treating steep bowls, spine-like features and tree lanes as canvases, linking fluid, fall-line turns with well-timed airs off natural lips and rollovers. He tends to favor three-dimensional terrain where he can use small pillows, wind lips and ribbed ridges to add variety, rather than just straightlining open faces. Landings are usually placed where the slope naturally catches him, which keeps his speed manageable and lets him link into the next feature without breaking rhythm.

On park and urban terrain, his Tahoe and OS Crew edits highlight a different but complementary side of his skiing. A 2019 season edit and Squaw park clips show him comfortable on sizeable booters, mixing straightforward spins with clean grabs and landings placed high on the transition. On rails and street features, he prefers lines that work with the spot rather than against it: gap-on entries that respect the run-in, surface swaps that follow the rail’s shape and exits that set him up for the next down, kink or stair set. Across both environments, a few technical traits stand out. He keeps his upper body calm and centered, lets his feet do the micro-adjustments on takeoff and landing, and commits to his edge or rail choice early instead of making last-second corrections.

Resilience, filming, and influence

Resilience is embedded in Feick’s role as both skier and filmmaker. Directing and editing a full-length backcountry film like “Bandits Unchained” means accepting that many days will end without a single usable shot—storms roll in, snowpack changes, sleds break and lines do not always go to plan. Yet the finished project still delivers nearly forty minutes of skiing and humor, a testament to his ability to keep a crew motivated, organized and creative over an entire winter. That same toughness appears in his OS Crew work, where late-night winch sessions, repeated crashes and constant shovel time are just part of getting a few seconds of usable street footage.

His influence also runs through the next generation. At Beartooth Big Mountain Summer Camp, Feick is part of a coaching staff that spends the summer on the Beartooth Pass, using the steep pitches and corn snow of the high plateau to teach teens and young adults how to move safely and confidently in freeride terrain. There he translates years of Squaw competition experience, Montana backcountry travel and OS-style creativity into line-choice lessons, crash analysis and practical guidance on building a sustainable life around skiing. Combined with his film work—including crossover projects like “Road House The Movie” from a summer based at Windells on Mt. Hood and bike pieces such as “End of the Beginning” about Calgary’s B-LINE bike park—this mentoring role means his ideas about style, risk and community travel far beyond his own turns.

Geography that built the toolkit

Feick’s skiing makes immediate sense when you look at the places that shaped him. Growing up around Palisades Tahoe meant cutting his teeth on a mountain famous for its big-mountain competition venues, cliff bands and wind-affected bowls. Those early Sugar Bowl and Squaw contests demanded comfort with variable snow, blind rollovers and judges who expect both aggression and control. Long before he was a filmmaker, he was a competitor and coach on some of North America’s most historic freeride slopes.

His move to Bozeman opened up a different flavor of mountains. Montana’s ski culture is built around places like Bridger Bowl, Big Sky and the surrounding backcountry—zones where long approaches, complex terrain traps and deep mid-winter storms are standard. The Montana Bandits films show him and his friends exploring those spaces, often using snowmobiles and skin tracks to reach pillow zones, couloirs and playful mini-golf faces. Seasonal migrations to Mt. Hood add another layer, with glacier laps and public-park sessions keeping his jump and rail skills sharp in summer. More recently, travel to Treble Cone and other New Zealand spots has introduced him to Southern Hemisphere winters, with their unique mix of big faces, variable snow and dramatic ridgelines. All of these regions leave fingerprints on his turns: Tahoe’s confidence in exposure, Montana’s love of pillows and trees, Hood’s park smoothness and New Zealand’s high-speed, big-arc energy.

Equipment and partners: practical takeaways

While Feick is not loudly associated with a single ski brand in the way some athletes are, his projects reveal a consistent, practical approach to equipment. In his 2019 season edit, he thanks a friend for lending him a pair of Armada skis for much of the Tahoe filming—a small detail that hints at a preference for versatile, twin-tip designs that feel comfortable both in the park and on natural features. In OS Crew films, he rides under a banner of partners that support the crew as a whole, including J Skis, Dakine, Roxa boots, Daymaker Touring and winch brands like ReWinch. Those credits point to a gear ecosystem built for long days filming: mid-fat twintips that can land on hard snow or deep pow, boots stiff enough for drops and rails but hike-friendly when the approach demands it, outerwear and packs suited to stormy Montana days and avalanche tools that are treated as standard, not optional.

For skiers looking to draw lessons from his setup, the key is coherence rather than brand replication. Feick’s work suggests building a quiver that can handle both big-mountain lines and creative side hits—a ski with enough width and rocker for Montana powder but a tail that still feels natural on takeoffs and landings, boots that balance response with all-day wear, and protective gear that you are willing to wear every session. If you are filming with friends, think in terms of durability and versatility: gear that can survive repeated bails on street rails, long snowmobile shuttles and spring slush at Hood while still letting you ski the way you want.

Why fans and progressing skiers care

Fans care about Jack Feick because he embodies a version of freeskiing that feels genuinely full-circle. He has stood in big-mountain start gates in Tahoe, chased street spots across the West Coast, guided viewers through Montana backcountry epics and helped coach the next generation at Beartooth Pass and the Yellowstone Club. His projects balance humor and seriousness, mixing “rowdy crew” antics with careful attention to avalanche terrain, line choice and the realities of long days in the mountains. When his name appears in the credits of an OS Crew film, a Montana Bandits project or a festival listing, viewers know they are about to see skiing that is both thoughtful and fun to watch.

For progressing skiers, Feick offers a concrete roadmap. Build strong fundamentals in whatever terrain you can access, learn to read mountains through freeride competitions or local big-mountain events, and do not be afraid to pick up a camera and start telling your own stories. Use summer parks like Mt. Hood to keep your tricks sharp, but let winter be about exploration as much as progression. Study his films to see how he chooses lines that fit the terrain, how he balances risk and reward and how he turns small crews and regional mountains into work that resonates across the freeski world. In an era where style, storytelling and community matter as much as raw difficulty, Jack Feick stands out as a rider–filmer–coach whose career captures what modern freeskiing is really about.