Jacob Wester

Profile and significance

Jacob Wester is a Swedish freeski original whose career traces the sport’s last two decades—from the dawn of doubles in park and big air to steep, foot-powered lines in the high Alps and Arctic Norway. Born in 1987 in Stockholm, he burst onto the scene with runner-up at the Jon Olsson Invitational in 2005, stacked wins at major showcases in 2008, and claimed Big Air bronze at the X Games in Aspen in 2009. Those contest years overlapped with film parts that traveled widely, including Matchstick Productions titles during the La Niña era and later projects that he directed and edited himself. In the mid-2010s Wester pivoted toward ski-mountaineering, documenting bold descents around Chamonix and the Lyngen Alps while keeping one boot in the media world through Real Ski Backcountry and YouTube vlogs. The through-line is clarity: whether it’s a switch double off a scaffolding jump or a no-fall couloir above glacial seracs, Wester favors mechanics that read at full speed and age well on a tenth watch.

Across results and films, he has served as a bridge between eras. Early mentorship and friendly rivalry with fellow Swede Jon Olsson helped push the “doubles movement” into the mainstream. Later, his transition to big mountains—often without helicopters, relying on skins, crampons, and timing—modeled a path for park athletes who want to climb and ski serious lines without losing style. By the 2020s, that dual identity made him a fixture in both rider-run web edits and marquee film tours.

Competitive arc and key venues

Wester’s competitive résumé is short but sharp. The breakout crest arrived in 2008 with wins at Freestyle.ch Zürich and the North American Open slopestyle in Breckenridge, followed by Big Air bronze at Winter X Games XIII in 2009. Aspen’s Buttermilk served as the stage where his measured spin speed, deep grabs, and calm outruns competed with the heaviest trick lists of the day. He later returned to the franchise in a different format with Real Ski Backcountry, contributing a filmed part instead of a judged stadium run—an early sign of the pivot to storytelling that would define his next chapter.

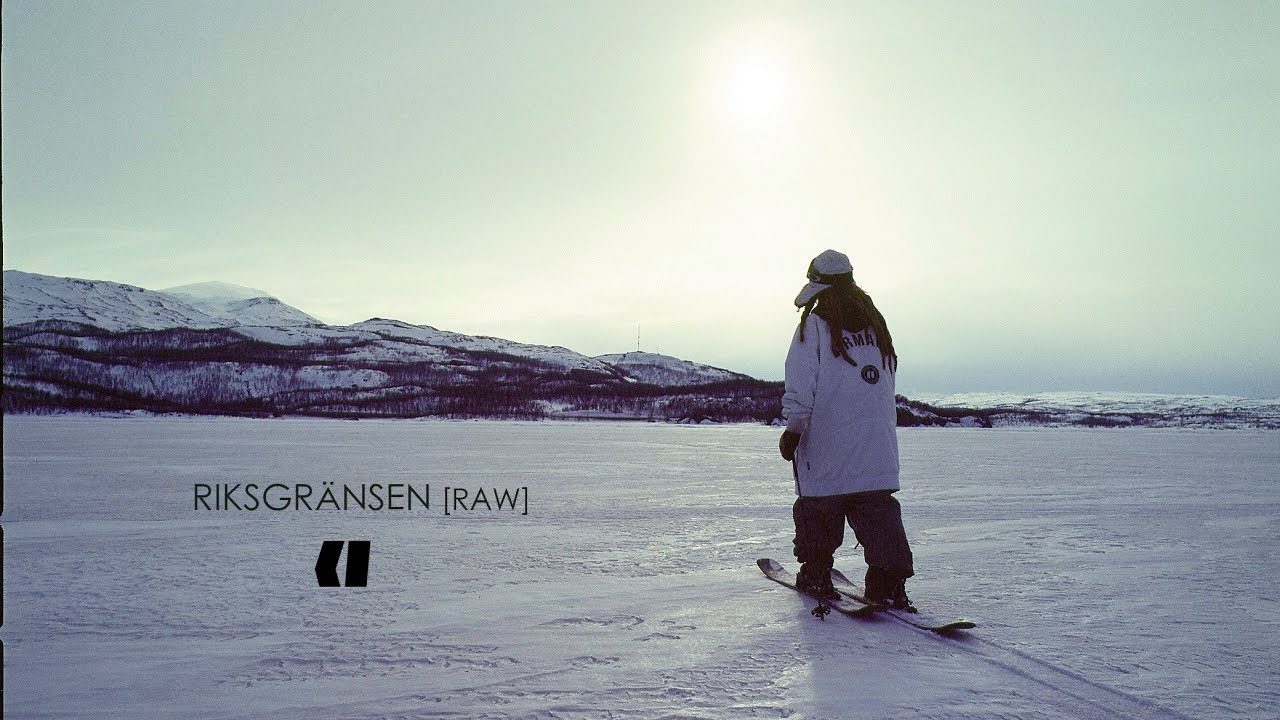

Film venues explain the second act. In 2010–11 he featured in Matchstick productions like “The Way I See It” and “Attack of La Niña,” before training his lens—and edges—on steeper ground. Around Chamonix, he skied prominent lines accessed from the Aiguille du Midi, threading features above the Vallée Blanche and the Pas de Chèvre. Farther north, he chased spring windows in Norway’s Lyngen Alps, where summit-to-sea terrain and fast-changing weather reward patience and exact reading of snow. In 2025 he appeared in Matchstick’s “After the Snowfall,” including a nerve-testing mission in Lyngen—evidence that the contest technician grew into a dependable big-mountain operator without shedding his park timing.

How they ski: what to watch for

Wester’s skiing is a study in readable difficulty. In the park and on man-made jumps, approaches square up early, grabs come in fast and stay long enough to stabilize the axis, and landings finish over the feet so the outrun breathes. That habit—treating the grab as a control input, not decoration—explains why his bigger spins look unhurried and why editors seldom need slow-motion rescue. On rails he favors decisive lock-ins and surface swaps that resolve cleanly; presses carry shape instead of wobble; exits protect speed for the next feature.

Transplanted into big mountains, the same habits show up as line literacy. He commits to entries early, trims speed with small, on-purpose checks instead of skids, and lets the ski run where terrain allows so momentum survives the next choke. In no-fall terrain, that economy keeps exposure from turning into panic. If you’re watching a Wester clip in real time, look for two cues: spacing between moves that preserves cadence, and hand-to-ski contact that quiets rotation or dampens chatter when the snow turns chalky.

Resilience, filming, and influence

Street and steep skiing share a requirement: patience. Wester’s output over the last decade shows a willingness to do the slow work—forecast watching, boot-packing, digging platforms, or walking away from objectives that don’t line up. That judgment is why his steep segments hold up under scrutiny and why partners keep calling when a project needs someone who can ski with composure and tell the story afterward. His Real Ski Backcountry appearance and a long string of self-produced edits demonstrated that contest skills can translate into narrative, while features with Matchstick and other crews gave those stories broad reach.

The influence runs in two directions. Park specialists looking for longevity study how he preserved his mechanics while expanding his canvas. Big-mountain skiers chasing fluency on airs copy his grab timing and centered exits to keep slashes and threes functional rather than flashy. Most of all, his career reframes “style” as technique you can practice: early commitments, functional grabs, tidy landings, and line choices that make sense the first time you see them.

Geography that built the toolkit

Place is the skeleton of Wester’s skiing. Stockholm’s small, icy hills gave him repetition and edge honesty. Contest travel refined broadcast composure at Buttermilk and rhythm on the long park lines of LAAX and Breckenridge. Then came the mountains that reshaped his identity. In Chamonix, the Aiguille du Midi changed scale and consequence; even “easy” ramps demand exact timing when exposure is real. In Norway, the Lyngen Alps offered kinetic summit-to-fjord terrain where snow, wind, and light shift by the hour. Stitch those environments together and you get a toolkit that travels: protect momentum, finish movements early, and let the line keep its shape from the first move to the last safety spot.

Equipment and partners: practical takeaways

Wester’s equipment history mirrors his phases. During the contest and early film years he rode athlete-driven platforms from Armada Skis—predictable swing weight for doubles, stable takeoffs, and edges that tolerated rail contact. As he migrated into the backcountry and then the steeps, you’d often see him on freeride setups from Rossignol, a category built for centered landings and trustworthy behavior in variable snow. For viewers translating lessons to their own kit, the specifics matter less than the fit: choose a ski that matches the job (symmetrical park tool for rails and jumps; directional freeride platform with dependable edge hold for couloirs), keep bases fast so cadence doesn’t depend on perfect weather, and tune edges to balance bite on ice with forgiveness at the tips and tails.

On the media side, long relationships with film outfits like Matchstick Productions underline a broader takeaway: pick partners and projects that let technique show. Whether the backdrop is a stadium jump, a spring park, or a shaded face above town, the camera should amplify the skiing instead of hiding it. That’s been Wester’s north star from Aspen to the Alps.

Why fans and progressing skiers care

Jacob Wester matters because he turned elite, early-2000s park difficulty into a durable language, then carried that language into consequential mountains without losing clarity. He has the medal to satisfy the stat sheet and the filmography to teach by example. If you’re a fan, his segments reward rewatching because the trick math is transparent. If you’re a skier in progression, his blueprint is actionable: square approaches, use the grab to control the axis, finish moves early enough to ride out centered, and make choices that protect speed so the line stays intact. That combination—results, readability, and range—is why his influence runs from Stockholm rope tows to Aiguille du Midi trams and up to the ridgelines of the Lyngen Alps.