Dick Barrymore

Profile and significance

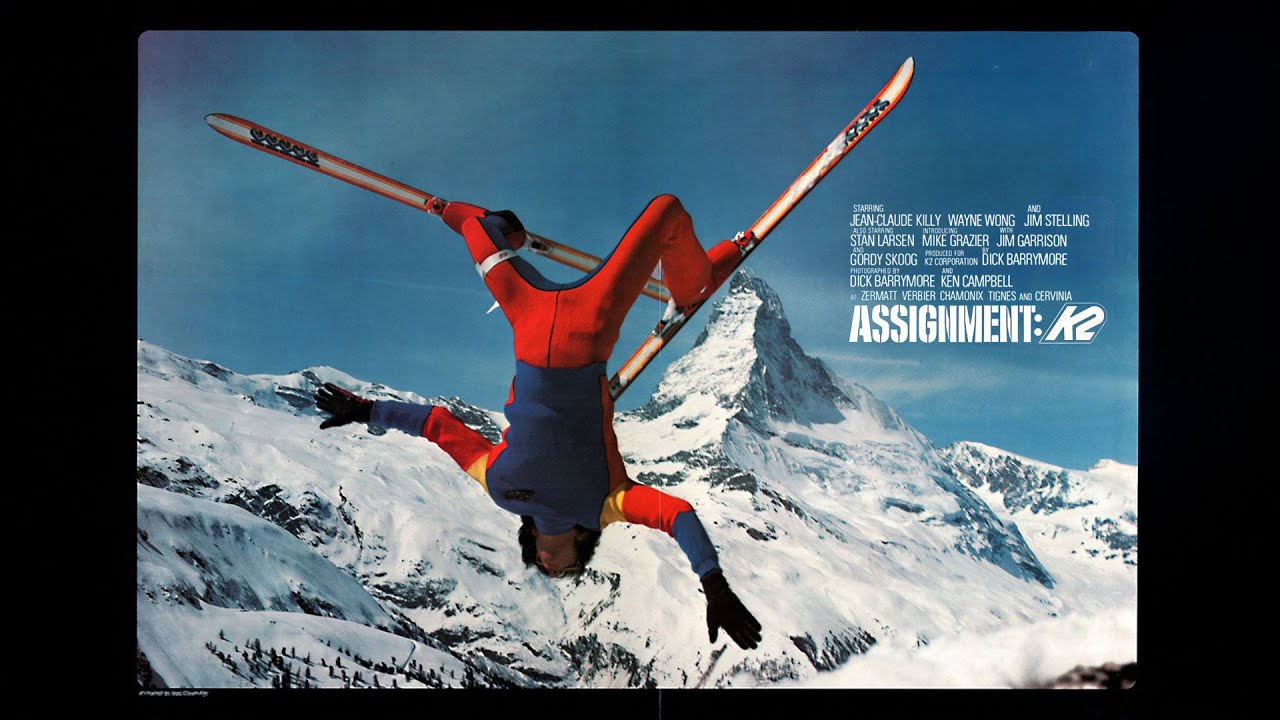

Dick Barrymore was one of the original architects of modern ski filmmaking, an American documentary filmmaker whose work in the 1960s and 1970s fundamentally changed how the world saw skiing. Born in Los Angeles in 1933 and later based in Idaho, he became famous for dynamic ski films that celebrated speed, powder, moguls and, crucially, the emerging “hot dogging” movement that would evolve into modern freestyle and freeski culture. Rather than simply recording racers on groomed hills, Barrymore turned his camera toward adventurous skiers pushing style and creativity on snow, then took those films on the road, narrating them live to packed halls across North America. Titles like “Last of the Ski Bums,” “Wild Skis” and “The Performers” helped define the tone of ski movies for a generation: funny, adventurous, a little rebellious and deeply in love with mountain life. His induction into the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame in 2000 confirmed what many skiers already knew—Barrymore was not just documenting ski culture, he was helping to build it.

For a freeski or freestyle fan today, Barrymore’s importance sits alongside better-known names from the competition world. The tricks and attitudes of slopestyle and big air, and even the pacing of urban and street skiing segments, owe a debt to the way he framed “hot dog” skiers: as characters with big personalities, linking expressive turns, aerials and stunts into full stories. His films also showed ordinary resort skiers what was possible off the beaten path, in deep powder and steep off-piste terrain, much of it far from the controlled world of racing. That mix of relatable humor and frontier energy is a big reason his work still matters to viewers who discover it decades later.

Competitive arc and key venues

Barrymore’s “competitive arc” did not play out in bibs and start gates, but on screens and in auditoriums. He began filming skiing around the time of the 1960 Winter Olympics, then leaned fully into his new path as a ski movie maker. Over the next three decades, he built a career traveling from resort town to resort town, screening his latest project in the evenings while gathering fresh footage by day. He was part of a small, tight-knit group of ski filmmakers who effectively toured like athletes, returning year after year to classic venues to capture better lines, deeper snow and more daring performances from the skiers they followed.

Sun Valley and nearby Ketchum became a long-term base, and the local mountains around Sun Valley Resort frequently appeared in his work. But Barrymore’s camera ranged far wider: European destinations such as the Alps, early heli-ski zones in western Canada and road-trip-friendly North American resorts all fed into his filmography. His collaborations with guides from operations that would later be known under the banner of CMH Heli-Skiing helped bring the adventure of big-mountain powder skiing to skiers who had only ever imagined it. Rather than counting medals or podiums, Barrymore’s “results sheet” is his sequence of influential films—from “Ski West, Young Man” through “Last of the Ski Bums,” “Vagabond Skiers” and many more—which effectively served as annual benchmarks for what was new and exciting in skiing.

How they ski: what to watch for

Barrymore was not primarily famous for his own turns, but his films showcase a distinctive approach to skiing that fans can still study. The skiers he chose to feature were rarely robotic race specialists; instead they were strong all-mountain athletes who treated the mountain as a playground, mixing powerful carved turns with bumps, cliffs and creative airs. Powder segments in his movies emphasize fluid, fall-line skiing, with long, arcing turns and full-face descents that feel almost continuous. Mogul scenes highlight quick feet, upright posture and a willingness to launch off troughs or knolls in ways that foreshadow modern big air and slopestyle sensibilities.

His hot-dogging sequences in particular provide a direct historical link to today’s freeskiing. Long before terrain parks and standardized jump lines, Barrymore’s cameras captured skiers performing front flips, spread eagles and spins on natural hits, snow mounds and rudimentary ramps. When you watch one of his films, pay attention to how the athletes use terrain transitions, not just the trick itself: they are reading fall lines, compressions and lips exactly the way a modern freeski or big-air rider does, just with simpler tricks and heavier gear. For anyone progressing toward freeride or freestyle skiing, those scenes are a reminder that strong fundamentals and terrain reading came first, with tricks layered on top.

Resilience, filming, and influence

From a production standpoint, Barrymore built his career on resilience and self-reliance. He often carried the camera himself, worked as his own editor and personally narrated his films, sometimes putting on dozens of live shows each season. Financially, it was a demanding model: he had to sell tickets in each town, maintain his equipment, and constantly gather fresh footage good enough to lure people back the following year. His memoir “Breaking Even” underlines how precarious that balance could be, but also how driven he was to keep skiing and filming on his own terms.

That persistence paid off in influence. Younger filmmakers and athletes absorbed his combination of humor, honesty and on-snow progression. Riders like Greg Stump and many others would later build on Barrymore’s foundation, pushing cinematic techniques and music choices even further but keeping the same basic promise: show real skiers doing bold things in real mountains. His work helped move ski films away from pure resort tourism reels and toward the athlete-driven, story-based films that now define freeski and freeride culture. At the same time, he was not afraid to show crashes, exhaustion or the logistics behind the shots, which gave audiences a more realistic sense of what it takes to ski at that level.

Geography that built the toolkit

Geography shaped Barrymore’s storytelling as much as it shapes an athlete’s skiing. Growing up in California and later basing himself in Idaho gave him easy access to very different mountains and snowpacks, from coastal ranges with dense storms to the drier, sunnier Northern Rockies. Life in and around Ketchum kept him close to the lifts, backcountry terrain and cultural energy of Sun Valley Resort, a place long associated with Hollywood stars and serious skiers alike. The resort’s mix of groomers, steeps and off-piste lines provided a natural laboratory for filming everything from classic alpine turns to powder and moguls.

Barrymore’s travels pushed even further afield. Collaborations with operations that would evolve into CMH Heli-Skiing took him into the deep, glaciated mountains of British Columbia, where endless tree runs and high alpine faces changed viewer expectations about what “a ski trip” could look like. He also extended his life beyond snow; developing Cabo Pulmo Beach Resort in Mexico gave him a warm-water contrast to winter, and his small-plane adventures there reinforced his identity as a lifelong explorer. That blend of Idaho roots, global ski travel and coastal side projects created a worldview where mountains, oceans and open roads all belonged in the same story.

Equipment and partners: practical takeaways

Barrymore’s films also offer a time capsule of ski equipment evolution and brand culture. His long-running association with K2 Skis, reflected in film titles like “Here Come the K2 Skiers,” chronicled the emergence of fiberglass skis and more playful shapes that allowed athletes to charge harder in powder, moguls and off-piste terrain. By repeatedly putting K2 athletes and products on screen, he helped show everyday skiers how new materials and designs could translate into confidence on steep or variable snow. The message was not just about marketing; it was about demonstrating that the right gear could expand what was possible on the hill.

His heli-ski segments with guides who would later be associated with CMH Heli-Skiing also highlighted the importance of robust, trustworthy gear in truly remote environments. Sturdy bindings, supportive boots and fat enough skis to float in deep snow were all part of the equation, but so was safety equipment tailored to avalanche terrain and helicopter logistics. Even without product close-ups or modern gear breakdowns, viewers could see that serious terrain demanded serious preparation. For today’s freeride, slopestyle and big-air fans, the practical takeaway is simple: gear matters, but it matters most as part of a coherent system that matches the terrain you aspire to ski, whether that’s a resort mogul run, a backcountry face or a small local hill where you are learning your first spins.

Why fans and progressing skiers care

Modern viewers care about Dick Barrymore because his films capture the moment when skiing shifted from a formal, race-centric pastime into something looser, more expressive and closer to today’s freeski culture. The hot-dogging he championed laid the groundwork for slopestyle, big air and even urban and street skiing, not in terms of exact tricks, but in the mindset that style, creativity and fun mattered just as much as results. His movies showed groups of friends traveling, living cheaply, chasing storms and inventing new ways to enjoy the mountain—an energy that many ski bums, content creators and aspiring pros still recognize in their own journeys.

For progressing skiers, Barrymore’s work is a reminder that progression is as much about curiosity and storytelling as it is about difficulty. You see skiers making the most of whatever terrain they have, linking modest features into memorable lines and laughing even when things go sideways. That attitude continues to influence how modern filmmakers and athletes frame their own segments, whether they are filming park lines, backcountry booters or street rails. Watching his films alongside contemporary freeski edits gives fans a longer arc of progression and a deeper appreciation for how ski culture reached its current blend of freeride intensity, slopestyle precision and everyday resort fun. In that sense, Dick Barrymore remains essential viewing for anyone who wants to understand not just how people ski today, but how we learned to dream about skiing in the first place.